Bush challenges hundreds of laws

President cites powers of his office

WASHINGTON -- President Bush has quietly claimed the authority to disobey more than 750 laws enacted since he took office, asserting that he has the power to set aside any statute passed by Congress when it conflicts with his interpretation of the Constitution.

Among the laws Bush said he can ignore are military rules and regulations, affirmative-action provisions, requirements that Congress be told about immigration services problems, ''whistle-blower" protections for nuclear regulatory officials, and safeguards against political interference in federally funded research.

Legal scholars say the scope and aggression of Bush's assertions that he can bypass laws represent a concerted effort to expand his power at the expense of Congress, upsetting the balance between the branches of government. The Constitution is clear in assigning to Congress the power to write the laws and to the president a duty ''to take care that the laws be faithfully executed." Bush, however, has repeatedly declared that he does not need to ''execute" a law he believes is unconstitutional.

Former administration officials contend that just because Bush reserves the right to disobey a law does not mean he is not enforcing it: In many cases, he is simply asserting his belief that a certain requirement encroaches on presidential power.

But with the disclosure of Bush's domestic spying program, in which he ignored a law requiring warrants to tap the phones of Americans, many legal specialists say Bush is hardly reluctant to bypass laws he believes he has the constitutional authority to override.

Far more than any predecessor, Bush has been aggressive about declaring his right to ignore vast swaths of laws -- many of which he says infringe on power he believes the Constitution assigns to him alone as the head of the executive branch or the commander in chief of the military.

Many legal scholars say they believe that Bush's theory about his own powers goes too far and that he is seizing for himself some of the law-making role of Congress and the Constitution-interpreting role of the courts.

Phillip Cooper, a Portland State University law professor who has studied the executive power claims Bush made during his first term, said Bush and his legal team have spent the past five years quietly working to concentrate ever more governmental power into the White House.

''There is no question that this administration has been involved in a very carefully thought-out, systematic process of expanding presidential power at the expense of the other branches of government," Cooper said. ''This is really big, very expansive, and very significant."

For the first five years of Bush's presidency, his legal claims attracted little attention in Congress or the media. Then, twice in recent months, Bush drew scrutiny after challenging new laws: a torture ban and a requirement that he give detailed reports to Congress about how he is using the Patriot Act.

Bush administration spokesmen declined to make White House or Justice Department attorneys available to discuss any of Bush's challenges to the laws he has signed.

Instead, they referred a Globe reporter to their response to questions about Bush's position that he could ignore provisions of the Patriot Act. They said at the time that Bush was following a practice that has ''been used for several administrations" and that ''the president will faithfully execute the law in a manner that is consistent with the Constitution."

But the words ''in a manner that is consistent with the Constitution" are the catch, legal scholars say, because Bush is according himself the ultimate interpretation of the Constitution. And he is quietly exercising that authority to a degree that is unprecedented in US history.

Bush is the first president in modern history who has never vetoed a bill, giving Congress no chance to override his judgments. Instead, he has signed every bill that reached his desk, often inviting the legislation's sponsors to signing ceremonies at which he lavishes praise upon their work.

Then, after the media and the lawmakers have left the White House, Bush quietly files ''signing statements" -- official documents in which a president lays out his legal interpretation of a bill for the federal bureaucracy to follow when implementing the new law. The statements are recorded in the federal register.

In his signing statements, Bush has repeatedly asserted that the Constitution gives him the right to ignore numerous sections of the bills -- sometimes including provisions that were the subject of negotiations with Congress in order to get lawmakers to pass the bill. He has appended such statements to more than one of every 10 bills he has signed.

''He agrees to a compromise with members of Congress, and all of them are there for a public bill-signing ceremony, but then he takes back those compromises -- and more often than not, without the Congress or the press or the public knowing what has happened," said Christopher Kelley, a Miami University of Ohio political science professor who studies executive power.

The Constitution grants Congress the power to create armies, to declare war, to make rules for captured enemies, and ''to make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces." But, citing his role as commander in chief, Bush says he can ignore any act of Congress that seeks to regulate the military.

On at least four occasions while Bush has been president, Congress has passed laws forbidding US troops from engaging in combat in Colombia, where the US military is advising the government in its struggle against narcotics-funded Marxist rebels.

After signing each bill, Bush declared in his signing statement that he did not have to obey any of the Colombia restrictions because he is commander in chief.

Bush has also said he can bypass laws requiring him to tell Congress before diverting money from an authorized program in order to start a secret operation, such as the ''black sites" where suspected terrorists are secretly imprisoned.

Congress has also twice passed laws forbidding the military from using intelligence that was not ''lawfully collected," including any information on Americans that was gathered in violation of the Fourth Amendment's protections against unreasonable searches.

Congress first passed this provision in August 2004, when Bush's warrantless domestic spying program was still a secret, and passed it again after the program's existence was disclosed in December 2005.

On both occasions, Bush declared in signing statements that only he, as commander in chief, could decide whether such intelligence can be used by the military.

In October 2004, five months after the Abu Ghraib torture scandal in Iraq came to light, Congress passed a series of new rules and regulations for military prisons. Bush signed the provisions into law, then said he could ignore them all. One provision made clear that military lawyers can give their commanders independent advice on such issues as what would constitute torture. But Bush declared that military lawyers could not contradict his administration's lawyers.

Other provisions required the Pentagon to retrain military prison guards on the requirements for humane treatment of detainees under the Geneva Conventions, to perform background checks on civilian contractors in Iraq, and to ban such contractors from performing ''security, intelligence, law enforcement, and criminal justice functions." Bush reserved the right to ignore any of the requirements.

The new law also created the position of inspector general for Iraq. But Bush wrote in his signing statement that the inspector ''shall refrain" from investigating any intelligence or national security matter, or any crime the Pentagon says it prefers to investigate for itself.

Bush had placed similar limits on an inspector general position created by Congress in November 2003 for the initial stage of the US occupation of Iraq. The earlier law also empowered the inspector to notify Congress if a US official refused to cooperate. Bush said the inspector could not give any information to Congress without permission from the administration.

In December 2004, Congress passed an intelligence bill requiring the Justice Department to tell them how often, and in what situations, the FBI was using special national security wiretaps on US soil. The law also required the Justice Department to give oversight committees copies of administration memos outlining any new interpretations of domestic-spying laws. And it contained 11 other requirements for reports about such issues as civil liberties, security clearances, border security, and counternarcotics efforts.

After signing the bill, Bush issued a signing statement saying he could withhold all the information sought by Congress.

Likewise, when Congress passed the law creating the Department of Homeland Security in 2002, it said oversight committees must be given information about vulnerabilities at chemical plants and the screening of checked bags at airports.

It also said Congress must be shown unaltered reports about problems with visa services prepared by a new immigration ombudsman. Bush asserted the right to withhold the information and alter the reports.

On several other occasions, Bush contended he could nullify laws creating ''whistle-blower" job protections for federal employees that would stop any attempt to fire them as punishment for telling a member of Congress about possible government wrongdoing.

When Congress passed a massive energy package in August, for example, it strengthened whistle-blower protections for employees at the Department of Energy and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

The provision was included because lawmakers feared that Bush appointees were intimidating nuclear specialists so they would not testify about safety issues related to a planned nuclear-waste repository at Yucca Mountain in Nevada -- a facility the administration supported, but both Republicans and Democrats from Nevada opposed.

When Bush signed the energy bill, he issued a signing statement declaring that the executive branch could ignore the whistle-blower protections.

Bush's statement did more than send a threatening message to federal energy specialists inclined to raise concerns with Congress; it also raised the possibility that Bush would not feel bound to obey similar whistle-blower laws that were on the books before he became president. His domestic spying program, for example, violated a surveillance law enacted 23 years before he took office.

David Golove, a New York University law professor who specializes in executive-power issues, said Bush has cast a cloud over ''the whole idea that there is a rule of law," because no one can be certain of which laws Bush thinks are valid and which he thinks he can ignore.

''Where you have a president who is willing to declare vast quantities of the legislation that is passed during his term unconstitutional, it implies that he also thinks a very significant amount of the other laws that were already on the books before he became president are also unconstitutional," Golove said.

Nonetheless, Bush has said in his signing statements that the Constitution lets him control any executive official, no matter what a statute passed by Congress might say.

In November 2002, for example, Congress, seeking to generate independent statistics about student performance, passed a law setting up an educational research institute to conduct studies and publish reports ''without the approval" of the Secretary of Education. Bush, however, decreed that the institute's director would be ''subject to the supervision and direction of the secretary of education."

Similarly, the Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld affirmative-action programs, as long as they do not include quotas. Most recently, in 2003, the court upheld a race-conscious university admissions program over the strong objections of Bush, who argued that such programs should be struck down as unconstitutional.

Yet despite the court's rulings, Bush has taken exception at least nine times to provisions that seek to ensure that minorities are represented among recipients of government jobs, contracts, and grants. Each time, he singled out the provisions, declaring that he would construe them ''in a manner consistent with" the Constitution's guarantee of ''equal protection" to all -- which some legal scholars say amounts to an argument that the affirmative-action provisions represent reverse discrimination against whites.

Golove said that to the extent Bush is interpreting the Constitution in defiance of the Supreme Court's precedents, he threatens to ''overturn the existing structures of constitutional law."

A president who ignores the court, backed by a Congress that is unwilling to challenge him, Golove said, can make the Constitution simply ''disappear."

Since the early 19th century, American presidents have occasionally signed a large bill while declaring that they would not enforce a specific provision they believed was unconstitutional. On rare occasions, historians say, presidents also issued signing statements interpreting a law and explaining any concerns about it.

But it was not until the mid-1980s, midway through the tenure of President Reagan, that it became common for the president to issue signing statements. The change came about after then-Attorney General Edwin Meese decided that signing statements could be used to increase the power of the president.

When interpreting an ambiguous law, courts often look at the statute's legislative history, debate and testimony, to see what Congress intended it to mean. Meese realized that recording what the president thought the law meant in a signing statement might increase a president's influence over future court rulings.

Under Meese's direction in 1986, a young Justice Department lawyer named Samuel A. Alito Jr. wrote a strategy memo about signing statements. It came to light in late 2005, after Bush named Alito to the Supreme Court.

In the memo, Alito predicted that Congress would resent the president's attempt to grab some of its power by seizing ''the last word on questions of interpretation." He suggested that Reagan's legal team should ''concentrate on points of true ambiguity, rather than issuing interpretations that may seem to conflict with those of Congress."

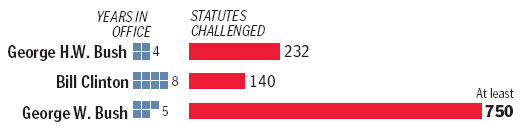

Reagan's successors continued this practice. George H.W. Bush challenged 232 statutes over four years in office, and Bill Clinton objected to 140 laws over his eight years, according to Kelley, the Miami University of Ohio professor.

Many of the challenges involved longstanding legal ambiguities and points of conflict between the president and Congress.

Throughout the past two decades, for example, each president -- including the current one -- has objected to provisions requiring him to get permission from a congressional committee before taking action. The Supreme Court made clear in 1983 that only the full Congress can direct the executive branch to do things, but lawmakers have continued writing laws giving congressional committees such a role.

Still, Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Clinton used the presidential veto instead of the signing statement if they had a serious problem with a bill, giving Congress a chance to override their decisions.

But the current President Bush has abandoned the veto entirely, as well as any semblance of the political caution that Alito counseled back in 1986. In just five years, Bush has challenged more than 750 new laws, by far a record for any president, while becoming the first president since Thomas Jefferson to stay so long in office without issuing a veto.

''What we haven't seen until this administration is the sheer number of objections that are being raised on every bill passed through the White House," said Kelley, who has studied presidential signing statements through history. ''That is what is staggering. The numbers are well out of the norm from any previous administration."

Defenders say the fact that Bush is reserving the right to disobey the laws does not necessarily mean he has gone on to disobey them.

Indeed, in some cases, the administration has ended up following laws that Bush said he could bypass. For example, citing his power to ''withhold information" in September 2002, Bush declared that he could ignore a law requiring the State Department to list the number of overseas deaths of US citizens in foreign countries. Nevertheless, the department has still put the list on its website.

Jack Goldsmith, a Harvard Law School professor who until last year oversaw the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel for the administration, said the statements do not change the law; they just let people know how the president is interpreting it.

''Nobody reads them," said Goldsmith. ''They have no significance. Nothing in the world changes by the publication of a signing statement. The statements merely serve as public notice about how the administration is interpreting the law. Criticism of this practice is surprising, since the usual complaint is that the administration is too secretive in its legal interpretations."

But Cooper, the Portland State University professor who has studied Bush's first-term signing statements, said the documents are being read closely by one key group of people: the bureaucrats who are charged with implementing new laws.

Lower-level officials will follow the president's instructions even when his understanding of a law conflicts with the clear intent of Congress, crafting policies that may endure long after Bush leaves office, Cooper said.

''Years down the road, people will not understand why the policy doesn't look like the legislation," he said.

And in many cases, critics contend, there is no way to know whether the administration is violating laws -- or merely preserving the right to do so.

Many of the laws Bush has challenged involve national security, where it is almost impossible to verify what the government is doing. And since the disclosure of Bush's domestic spying program, many people have expressed alarm about his sweeping claims of the authority to violate laws.

In January, after the Globe first wrote about Bush's contention that he could disobey the torture ban, three Republicans who were the bill's principal sponsors in the Senate -- John McCain of Arizona, John W. Warner of Virginia, and Lindsey O. Graham of South Carolina -- all publicly rebuked the president.

''We believe the president understands Congress's intent in passing, by very large majorities, legislation governing the treatment of detainees," McCain and Warner said in a joint statement. ''The Congress declined when asked by administration officials to include a presidential waiver of the restrictions included in our legislation."

Added Graham: ''I do not believe that any political figure in the country has the ability to set aside any . . . law of armed conflict that we have adopted or treaties that we have ratified."

And in March, when the Globe first wrote about Bush's contention that he could ignore the oversight provisions of the Patriot Act, several Democrats lodged complaints.

Senator Patrick J. Leahy of Vermont, the ranking Democrat on the Senate Judiciary Committee, accused Bush of trying to ''cherry-pick the laws he decides he wants to follow."

And Representatives Jane Harman of California and John Conyers Jr. of Michigan -- the ranking Democrats on the House Intelligence and Judiciary committees, respectively -- sent a letter to Attorney General Alberto R. Gonzales demanding that Bush rescind his claim and abide by the law.

''Many members who supported the final law did so based upon the guarantee of additional reporting and oversight," they wrote. ''The administration cannot, after the fact, unilaterally repeal provisions of the law implementing such oversight. . . . Once the president signs a bill, he and all of us are bound by it."

The courts have little chance of reviewing Bush's assertions, especially in the secret realm of national security matters.

''There can't be judicial review if nobody knows about it," said Neil Kinkopf, a Georgia State law professor who was a Justice Department official in the Clinton administration. ''And if they avoid judicial review, they avoid having their constitutional theories rebuked."

Without court involvement, only Congress can check a president who goes too far. But Bush's fellow Republicans control both chambers, and they have shown limited interest in launching the kind of oversight that could damage their party.

''The president is daring Congress to act against his positions, and they're not taking action because they don't want to appear to be too critical of the president, given that their own fortunes are tied to his because they are all Republicans," said Jack Beermann, a Boston University law professor. ''Oversight gets much reduced in a situation where the president and Congress are controlled by the same party."

Said Golove, the New York University law professor: ''Bush has essentially said that 'We're the executive branch and we're going to carry this law out as we please, and if Congress wants to impeach us, go ahead and try it.' "

Bruce Fein, a deputy attorney general in the Reagan administration, said the American system of government relies upon the leaders of each branch ''to exercise some self-restraint." But Bush has declared himself the sole judge of his own powers, he said, and then ruled for himself every time.

''This is an attempt by the president to have the final word on his own constitutional powers, which eliminates the checks and balances that keep the country a democracy," Fein said. ''There is no way for an independent judiciary to check his assertions of power, and Congress isn't doing it, either. So this is moving us toward an unlimited executive power." ![]()